#24 The 2020 HDR

This week, the UNDP's Human Development Report 2020 was published. I read these reports from A to Z, back when the website wasn't as fancy.* And as I mentioned on Twitter, I believe every social and cultural leader should study the HDR this year and take its messages to heart. There are countless links to debates in our sector, including the appreciation of indigenous knowledge and intangible heritage. Rooted in 'facts,' the HDR provides compelling arguments for our work. And multiple calls to action.

Unlike so many other UN publications, the HDR typically doesn't mince words. It's hard to sugarcoat facts, especially when they tend to be as shocking as the HDR's.

This will be a long newsletter. The report is 412 pages long (quite some notes), so what would you expect. I also take some detours and quote in its entirety the most astonishing story I have heard in years of working on cultural storytelling.

TL;DR: There is today a pressing need for inclusive human development, but in balance with the planetary boundaries. Not just pressing… acute. "The world is moving far too slowly towards advancing human development while easing planetary pressures." We've passed the point where we can rely on anything else (e.g., nature, global systems). We need to fix this ourselves—all of us.

(* I do love that the CIA World Fact Book website is still old school. I used to use this in parallel to the HDR to understand the countries behind the facts. For an agency clearly adept at technology, having this 90s website still up and running is terrific.)

The oldest story ever told

Let's not bury the lead and start with the most astonishing story, told by David Farrier, author of Footprints: In Search of Future Fossils (A book I've gifted a few times but haven't read. If anyone has a copy to spare, please!)

The Gunditjmara people of southeastern Australia have a tale of four giants, creators of the early Earth, who arrived on land from the sea. Three strode off to other parts of the country, but one stayed behind. He lay down, and his body took the form of a volcano, called Tappoc in the Dhauwurd Wurrong language, while his head became another, called Budj Bim. When Budj Bim erupted, so the story goes, "the lava spat out as the head burst through the earth forming his teeth."

The story occurs in the Dreaming, the mythic time in which the world was made, according to indigenous Australian cultures. But we can also place it in geological time. The discovery of a stone axe beneath tephra layers deposited when Budj Bim erupted around 37,000 years ago suggests that humans were living in the area and therefore could have witnessed the eruption. It would have been sudden; scientists think the volcano might have grown from ground level to tens of metres high in a matter of months or even just weeks. Other Gunditjmara legends describe a time when the land shook and the trees danced. Budj Bim could be the oldest continually told story in the world.

Many indigenous Australian peoples are thought to have lived on the same land for almost 50,000 years. It is difficult to imagine that life in the developed world, governed by the propulsion of technological innovation and the spasms of election cycles, is as deeply embedded in time. Yet the cumulative effect of our occupation will be a legacy imprinted on the planet's geology, biodiversity and atmospheric and oceanic chemistry that will persist for hundreds of thousands of years—and in some cases even hundreds of millions.

A better number than GDP

Some background to understanding the Human Development Index, the central number in the HDR.

GDP, or Gross Domestic Product, as is well-known, is a very crude indicator of a country's economic achievements. Let alone its overall achievements. Yet, as it is a number that is available, it is underlying countless decisions by governments and others. In the late 1980s, fed up with the flaws of GDP, Mahbub ul Haq proposed a rival indicator — that of human development. It would still be vulgar as an indicator but would contain more relevant information than the GDP managed to do. This became the HDI.

The Nobel-prize laureate Amartya Sen relates the HDI's founding history, its strengths, and the shortcomings in the 2020 HDR. In 1990, the HDI led to the first HDR.

"It is people, not trees, whose future choices have to be protected," affirmed the first Human Development Report, published in 1990. By setting human flourishing as the ultimate end of development, it asserted that development is not about the accumulation of material or natural resources. It is about enlarging people's ability to be and do what they have reason to value and expanding wellbeing freedoms.

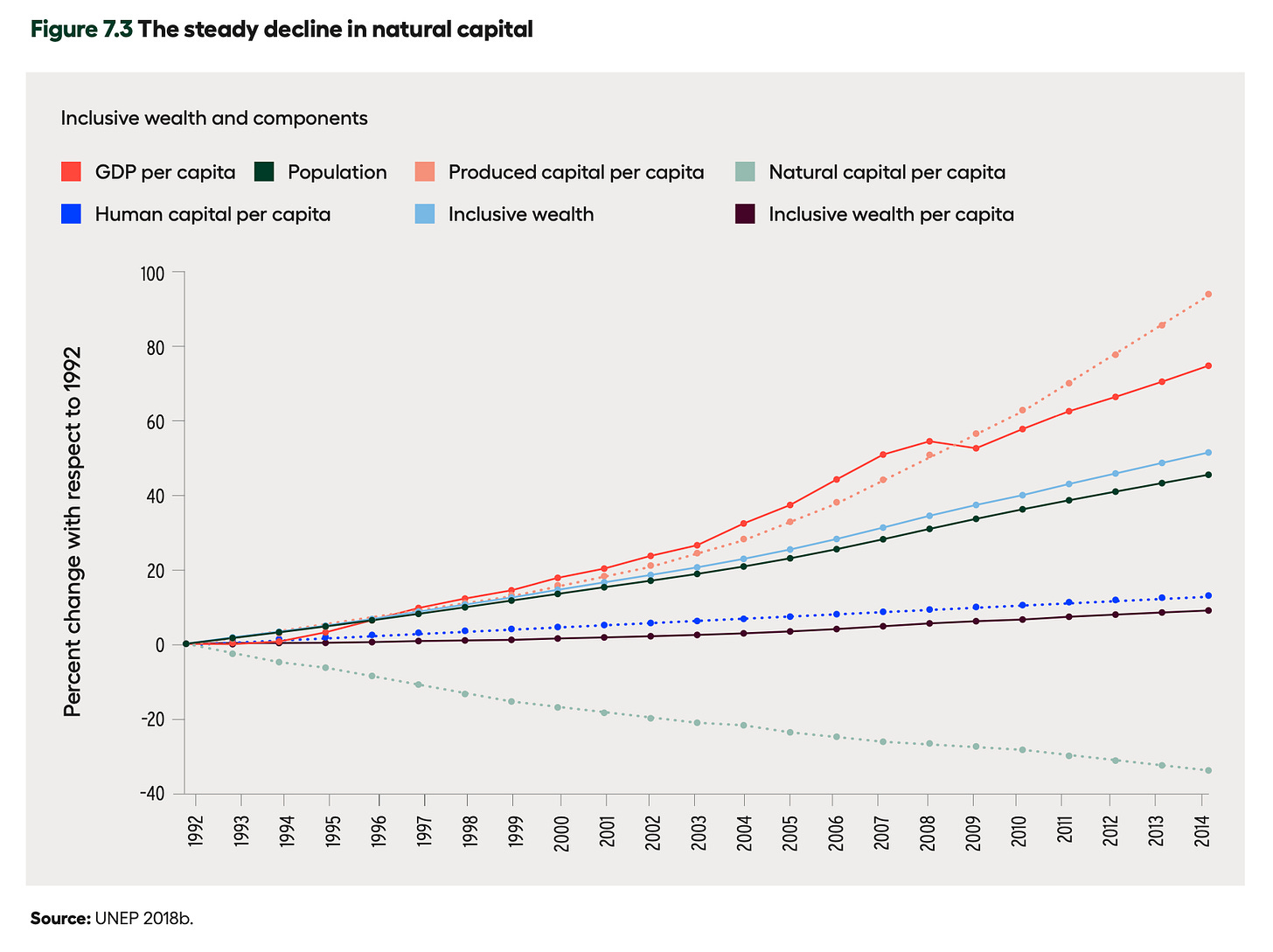

For thirty years, the HDI presented a competing vision to GDP when it came to development investments. It tells broad stories in a single metric: Ireland's rise, Venezuela's demise, Norway's hegemony. Now, however, once again, the indicator proves too crude. "Most people now live longer and healthier lives than their predecessors, but the opposite is true for the vast majority of the rest of life on Earth."

Therefore, the 2020 HDR presents a new metric: The Planetary pressures–adjusted Human Development Index. It is a masterstroke and pulls the rug out from under 75 years of human development policy and practice. As the authors state, "The adjustment to the HDI is a signaling device for positive change, encouraging the expansion of capabilities while reducing planetary pressures."

It is meaningful to note that human development and planetary wellbeing are intrinsically linked. Humans have become the dominant force on earth. Planetary and social imbalances reinforce each other. In countries with high ecological threats, there is also greater social vulnerability and vice versa.

As with all pressures and imbalances, COVID-19 acts as a magnifying glass. Please understand that "green" in the image below doesn't mean economic growth, but positive human development:

But we shouldn't blame Corona for the situation we find ourselves in. Across a wide range of indicators, inequalities were already increasing before February 2020. The inflection point in the trajectory of progress is due to multiple factors: stagnant or deteriorating economic conditions, many countries' weak positions in global value chains, and large inequalities in the distribution of income, assets, and resources.

Art and culture as a mechanism of change

Culture is the values, ideas, and practices that people share, and the expressions – including art – these inspire. Central in the 2020 HDR's roadmap for a better future is a call for a cultural shift, a reevaluation of the values, ideas, and practices that define our development in the future. Because no matter how dire the circumstances:

We [cannot] simply assume that expanding agency on its own means that more empowered people will invariably choose, individually and collectively, to avoid dangerous planetary change. Values, especially how they stack up and interact, help provide the overall direction for the choices that empowered people make about their lives. Values are fundamental to our personal understanding of what it means to live a good life. But people cannot realize their values without having sufficient capabilities and agency.

(…)

The Report argues that to navigate the Anthropocene, humanity can develop the capabilities, agency and values to act by enhancing equity, fostering innovation and instilling a sense of stewardship of nature. If these have greater weight within the ever widening choice sets that people create for themselves—if equity, innovation and stewardship become central to what it means to live a good life—then human flourishing can happen alongside easing planetary pressures.

Working with art and culture on sustainable development, I've come to see action on the development agenda as having various dimensions. There is the technological dimension, for instance, when it comes to innovation in energy generation. There is a political dimension and an economic dimension. But sustainable development also has a cultural and social dimension: people's attitudes and behaviors, values, and assumptions need to change in parallel with these other dimensions.

And while technology, politics, and the economy have found ways to work together and empower each other, the cultural and social dimension is often not more than an afterthought. This is partly due to our inability to tell our own story. Culture, after all, is sort of like the fourth Musketeer of the Triple Helix.

In a conversation with Yanis Varoufakis in Everything must change! Brian Eno says, "We all understand why food and exercise are important, but not art, and that's partly because the people who traditionally talk and write about art are such bad thinkers. They are so unclear in the way that they think and articulate." Ouch.

What do art and culture do? Eno says that art is a way to continue playing throughout your life. Essential, indeed, but culture and art add value on a deeper level: they increase the entropy in a system and, therefore, the number of possible futures. The 2020 HDR has the following to say about that:

The homogenizing effect of our predominant models of production and consumption, which have been busy knitting the world together, have eroded the diversity —in all its forms, from biological to cultural—that is so vital to resilience. Diversity increases redundancy, and while redundancy may not be good for business, it is good for system resilience in the face of shocks, which travel along the lines that connect people and nations.

Unfortunately, biodiversity loss often parallels the loss of cultural and language diversity, impoverishing societies culturally. While we need culture more, we have less of it available.

The 2020 HDR is crystal clear about where to look for diversity and successful approaches in balancing human development with planetary care:

Over the past few decades indigenous peoples have been on the front line of defending the Amazon rainforest. Territories across nine countries sharing the Amazon Basin and managed by indigenous peoples barely lost stored carbon between 2003 and 2016 (a fall of 0.1 percent), reflecting minor forest loss. Protected areas not managed by indigenous peoples experienced a loss of 0.6 percent. The rest of the Amazon experienced a loss of 3.6 percent.

The large-scale indigenous peoples' contribution to carbon storage is an example of how local decisions and nature-based solutions can substantially ease planetary pressures.

Rethinking the Anthropocene

A core concept in the HDR is the Anthropocene. I thought this was past its prime as a buzzword, but I may have been working a bit too much with natural history museums. Nonetheless, the report offers some fresh perspectives on the human-made timescale:

The Anthropocene represents an unprecedented convergence of the timescales of human lives with those of historical, evolutionary and geological processes.

And some disastrous facts:

In the Anthropocene biosphere, humans and livestock that is bred for human consumption outweigh all vertebrates combined (excluding fish), the mass of humans is an order of magnitude higher than that of all wild mammals and the biomass of domesticated poultry (dominated by chicken) is about three times that of all wild birds. Rates of species extinction are estimated to be hundreds or thousands of times higher than background rates—that is, the rates that would be expected without human interference (figure 2.3).

Now, in the context of the Anthropocene, it is essential to do away with stark distinctions between people and planet. Earth system approaches increasingly point to our interconnectedness as socioecological systems, a notion highly relevant to the Anthropocene.

Values as agents of change

I mentioned new values as a way to balance human development and planetary wellbeing. The 2020 HDR suggests three values: equity, innovation, and stewardship of nature. Innovation should be understood not merely in terms of Silicon Valley, but mostly as the embracing of indigenous and local solutions.

People can be agents of change if they have the power to act. But they are less likely or able to do so in ways that address the drivers of social and planetary imbalances if they are left out, if relevant technologies are not available or if they are alienated from nature. Conversely, equity, innovation and stewardship of nature each—and, more importantly, together—can break the vicious cycle of social and planetary imbalances (figure 3.1).

Equity, innovation, and stewardship of nature:

In sum, greater equity can be a powerful social stabilizing force and ease environmental pressures. It is not the only factor, and enhancing equity alone may not lead to these outcomes. That is why, along with equity, it is crucial to empower people through innovation and a sense of stewardship of nature.

(…)

Stewardship of nature echoes the often-unheard voices of indigenous peoples and the many communities and cultures over human history that see humans as part of a web of life on the planet. Evolution has encoded the lessons of billions of years in the biodiversity surrounding us. We depend on this biodiversity, even though we are accelerating its destruction. Instilling a sense of stewardship of nature can empower people to rethink values, re-shape social norms and steer collective decisions in ways that ease planetary pressures.

Where do these values come from? The report encourages looking in a direction that few UN publications have pointed to before, and one that immensely interests me (and can be of interest to anyone dealing with cultural heritage, storytelling, or art):

Stewardship can be supported by considering philosophical perspectives that value both thriving people and a thriving planet. This requires understanding how the relationship is and has been manifest in philosophical traditions, ancient knowledge (some- times codified in religions and taboos) and social practices. Many religions around the world and over time—including Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Islam and Judaism—have developed complex views of intergenerational justice and shared responsibility for a shared environment. The Quaranic concept of "tawheed," or oneness, captures the idea of the unity of creation across generations. There is also an injunction that the Earth and its natural resources must be preserved for future generations, with human beings acting as custodians of the natural world. The encyclical Laudato Si, issued in 2015, provides a Christian interpretation that speaks also to our embeddedness in nature and the notion of the planet as our common home, which we have a moral obligation to protect.

I expected Tikkun Olam here, the Jewish aspiration to heal the world. But it is not just religion that offers the framework for these new values:

In Aotearoa, New Zealand, the notion of "whakapapa" (to place in layers) sets out the connections among people, ecosystems, and all flora and fauna. The practices of "manaakitanga" (to care for) and "kaitiakitanga" (multispecies and intergenerational trusteeship) play key roles in articulating the responsibilities that fall out of these relationships.

Of course, it is beautiful to know that religions and indigenous practices and beliefs can save us from ourselves. But having the right values mentioned somewhere (espoused is the word) is not going to help us unless we enact them. We need to translate equity, innovation, and stewardship of nature into understandable behavior and guidelines that inform all our actions at scale. These values need to grow faster and further than Facebook.

So how can we encourage change in social norms in a context of strong values, weak agency and easy free riding? And who is best equipped to do so? One perspective on collective action is that an external entity needs to take this role, enforcing rule compliance. But alternative approaches show that self-organization can also be effective. Specifically, the organization in polycentric systems of governance—"several centers of decision-making which are formally independent of each other"—can mitigate collective action problems that many large administrations face. Each unit, such as a family, a company or a local government, establishes norms and rules with considerable independence. Chapters 1, 3 and 6 documented the numerous communities around the world, particularly indigenous peoples, that have preserved both cultural and biological diversity. Part of the explanation for their effectiveness is that they integrate local knowledge, peer learning and trial-and-error learning. Since they act at the local level, they also benefit from some social success factors because in smaller entities it is possible to establish trust and reciprocity, which foster agency and collective action, often without needing external enforcement and sanctions.

I'm of the school that believes people as members of various communities can be positive change agents. That is why I ended up working at the crossroads of culture and society. It is also why I believe in radical democratic processes, especially at the local level and within organizations.

An existential threat

The sentence "an existential threat" suffers from devaluation, a bit like the ten emails I get daily with breaking news. Currently, we're facing somewhere between 3 and 5 manmade (no gender-inclusive writing needed) existential threats. The Doomsday Clock mentions nuclear war, climate change, and cyber-enabled information warfare, Noam Chomsky adds the deterioration of democracy, and the 2020 HDR notes engineered pandemics.

All of them are compounded by our inability to mobilize en masse. This is odd because, by and large, we care. Also, there is a strong case to be made for the cumulative impacts that local initiatives can have at global levels regarding nature-based human development. This is where we act with Stichting 2030.

For example:

Multiple studies have documented the effects of urban green areas on cooling cities. In Nagoya, in central Japan, temperatures were up to 1.9 degrees Celsius higher in urban areas than in green areas. Differences were larger during the day than at night, and greater during the summer. In the winter temperature differences fell due to the loss of tree foliage, which reduces shading and evapotranspiration, causing a relative increase in green space air temperature and a decrease in differences with urban area temperatures. The cooling effect of green areas appeared to extend 200–300 metres from the green area into urban areas at night and 300–500 metres during the day. A study in London assessing the cooling effects of a large urban green space found that the mean temperature difference between urban and green spaces was about 1.1 degrees Celsius in the summer—and as much as 4 degrees on some nights—with the estimated cooling reaching 20–440 metres into the urban area.

As a side-note, last week, I visited the opening of a new urban greening project in Leiden. Currently, over 2,400 such projects have been initiated by citizens in their neighborhoods. Individually, each of these projects makes a street look a bit better. Collectively, they have a considerable impact on the quality of life in the city.

At the same time, we need to acknowledge that only some small initiatives here and there will not suffice. Earlier this year, I became serious about collecting litter from our neighborhood's streets and have collected some 500 kilos now. It makes me feel good (and it is quite addictive), but it is far from sufficient to improve the planet.

Achieving sustainable development, and even meeting the Sustainable Development Goals, will require more than adaptations and gradual changes. It will require transformations that break current locked-in systems of unsustainability. Measures aimed solely at reducing carbon dioxide emissions and slowing biodiversity loss, for example, equate to "doing less bad" but do not represent "doing right." Compensation and offsetting mechanisms might have behavioural benefits—helping recognize the costs of specific unsustainable activities.

But, who wins the prize?

The 2020 HDR is full of insights, but there's one that everybody will look for immediately: what is the score of my country? Norway is one again in HDI. In PHDI, the planetary-pressures adjusted metric, it's Ireland. The truth of the matter is, though, all of the very high HDI countries are losers. All of them are utterly unsustainable.

One last graph stands out to me. It is deep in the report, figure S7.2.6. It shows the share and growth in emissions of different groups of income earners worldwide. Unlike what you may have imagined from the graph above, it's the Western bottom and middle-class people that have been the only ones that achieved a reduction in emissions. One solution for human development and planetary balance this graph suggests is to (carbon) tax the global top 1% into oblivion and use the additional resources to raise the bottom 50% out of poverty. It is not that simple, but it is also not much more difficult.

Thanks for subscribing to my newsletter, reading it, and making it to the very end of this long, long story. I would have loved to write even more about the must-see movie Mosul on Netflix, the 60 songs that define the 90s, some successes we had this week with Stichting 2030, and some things that I had hoped to achieve by now but haven't. All of that, and more, a next time.

— Jasper