#119 The Gates Are Opening

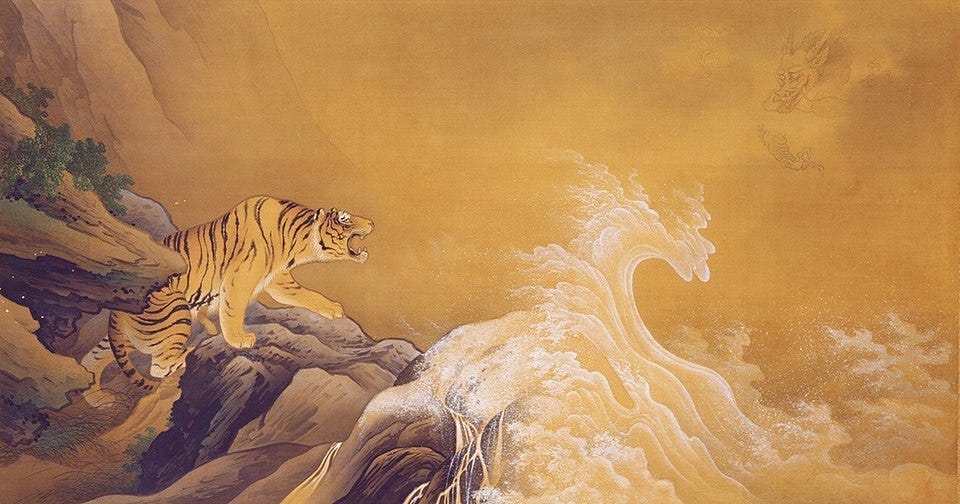

In the late 19th century, Japanese educator and philosopher Yukichi Fukuzawa wrote a remarkable insider’s account of one of history’s great transitions. Living through the Meiji period, Fukuzawa witnessed Japan’s rapid transformation from an isolated feudal society into a modern, globally connected nation. His book is also an autobiography, tracing his journey from impoverished samurai to renowned scholar. In that sense, it reads like a manifesto for self-realisation through education — a rejection of rigid hierarchies, and an embrace of openness: to the world, to new ideas, and to the values of individual agency. In Dutch, the book carries the evocative title De poorten gaan open — The Gates Are Opening. Years ago, my in-laws gave me a copy.

It’s tempting to read Fukuzawa through the lens of hindsight — to weigh his views on equality, individualism, and Westernisation against later chapters of Japan’s history. But I won’t. He died long before Japan’s global entanglements led to wars he would never have championed. The transition he documents is one of opening — of turning toward opportunity through curiosity, connection, and personal responsibility. That’s the kind of “opening up” I want to talk about today.

Institutional

Next month marks my three-year anniversary at BAM. In that time, I’ve seen the company change in real and measurable ways. After being named by climate advocacy group Milieudefensie as one of the Netherlands’ major polluters, our initial focus was clear: reduce our direct environmental impact. And with success. Operational emissions have been cut by double-digit percentages year on year. At the same time, we’ve increased our positive contribution to the world around us — often through decisions made within our own walls, using the tools of existing hierarchies and systems.

But even our boldest internal actions barely scratch the surface of our total impact. While we’ve reduced tens of kilotons of emissions annually, our indirect footprint — from materials, mobility, and beyond — is measured in megatons. Addressing that demands something else entirely: a different kind of organisation.

Yes, we’ve always worked with clients and suppliers — we’re a contractor, after all. But over the past year, something has shifted. We’ve found a new confidence in collaboration, and we’re beginning to open up. This week, for example, we announced a multi-year partnership with Into The Great Wide Open, a pioneering sustainability-focused festival. It’s just one sign that we’re reaching beyond our sector — seeking out ideas, energy, and alliances in unexpected places.

Professionally, I now spend much of my time not only with clients and colleagues, but also with competitors and civil society — building the conditions for shared success, not just market share. Moving forward means rethinking hierarchies, reimagining collaboration, and taking open innovation seriously. If we want to thrive in the years ahead, we must open our gates — to the world, to each other, and to what none of us can achieve alone.

Personal

In my early years at BAM, the focus on reducing our environmental footprint gave me a kind of clarity I hadn’t felt in a long time. My academic background had trained me to stay informed about everything — politics, culture, global affairs. Working internationally only reinforced that habit: my mental bandwidth was always full. But at BAM, something shifted. For the first time in years, I allowed my curiosity to narrow. I became radically focused — on asphalt, concrete, heavy machinery. Luckily, there was plenty to learn.

In parallel, I started a private challenge: to learn 50 new things before I turn 50. Running, guitar, magic tricks — isolated skills requiring more dedication than reflection. But now that I know the ABCs of construction and can fumble through More Than Words, something deeper is resurfacing. My studies are kicking back in. I’ve begun to see the harder things I still want to learn: how to age into fatherhood and partnership. How to make and keep close friends. How to lead anyone, anywhere.

None of these are automatic. For instance, I hadn’t grasped the danger of the resurgent patriarchy until I watched Adolescence and listened to therapists unpack the appeal of the Manosphere. I joined a leadership programme, confident in my “why,” “what,” and “how” — only to discover I still had little idea how to put them into practice. So I’ve started opening up: experimenting, showing up, saying yes to committees, platforms, and real conversations — not just with people like me, but across difference. If I want to be part of a more open world, I need to become a more open person.

Societal

Fukuzawa wrote about individual and institutional awakening but what makes his story enduring is that it’s ultimately about a society learning to open up. And that’s the level where I think we’re most in need of courage today. The personal and professional forms of openness I’ve described only matter if they contribute to something larger.

As I was reducing emissions and learning bar chords, the world around me seemed to be shutting down — borders closing, climate action defunded, inclusive values dismissed. As a progressive, I often hope this is the last gasp of an outdated worldview. But as a contrarian, I know better. Both progressives and conservatives are dreamers. Some long for a romanticised past. I long for an imagined future.

Part of my own opening up has been learning to truly listen to conservative thinkers — not to agree, but to understand. Where I see the past as a source of exclusion, crisis, and inequality, others see a time of cohesion, stability, and meaning. We can’t ignore that. Somewhere along the way, progressives made the future sound like a burden — all sacrifices, rules, and guilt. We forgot to make it seductive.

If we want people to move forward, we’ll need more than new policies. We’ll need new stories. That will require imagination, discomfort, and some very different thinking. We may even need to borrow a trick or two from conservatives — especially when it comes to designing a future people actually want to live in.

The Meiji-era reforms were controversial. But Fukuzawa saw in them the seeds of a society that could honour tradition while embracing modernity. His memoir is, in that sense, a quiet manifesto — a record of opportunity unlocked by openness. That’s the spirit we need today.

I believe the coming years will demand more than conviction. They will demand complexity. The future won’t be idealistic in one direction. It will be plural, messy, even contradictory. And that’s what makes it worth striving for. It also makes it a hard sell.

I’m energised by my employer’s turn to curiosity, collaboration, and responsibility. It’s worth noting that our sustainable progress has gone hand in hand with strong financial performance — proof that doing good and doing well aren’t at odds. Privately, it’s been a relief to shift from trying to know everything, to knowing some things deeply. Now, I want to build on those experiences to help create a world where I can once again visit Moscow in May, fly across the Atlantic for work on DEI, and take pride in my country’s progressive example to the world.

A world where we’ve tackled climate change and built fairer, more curious societies. A world that’s open. Not just in theory, but in practice. A future more attractive — and more possible — than any past we can remember.

Until then,

All the best,

Jasper